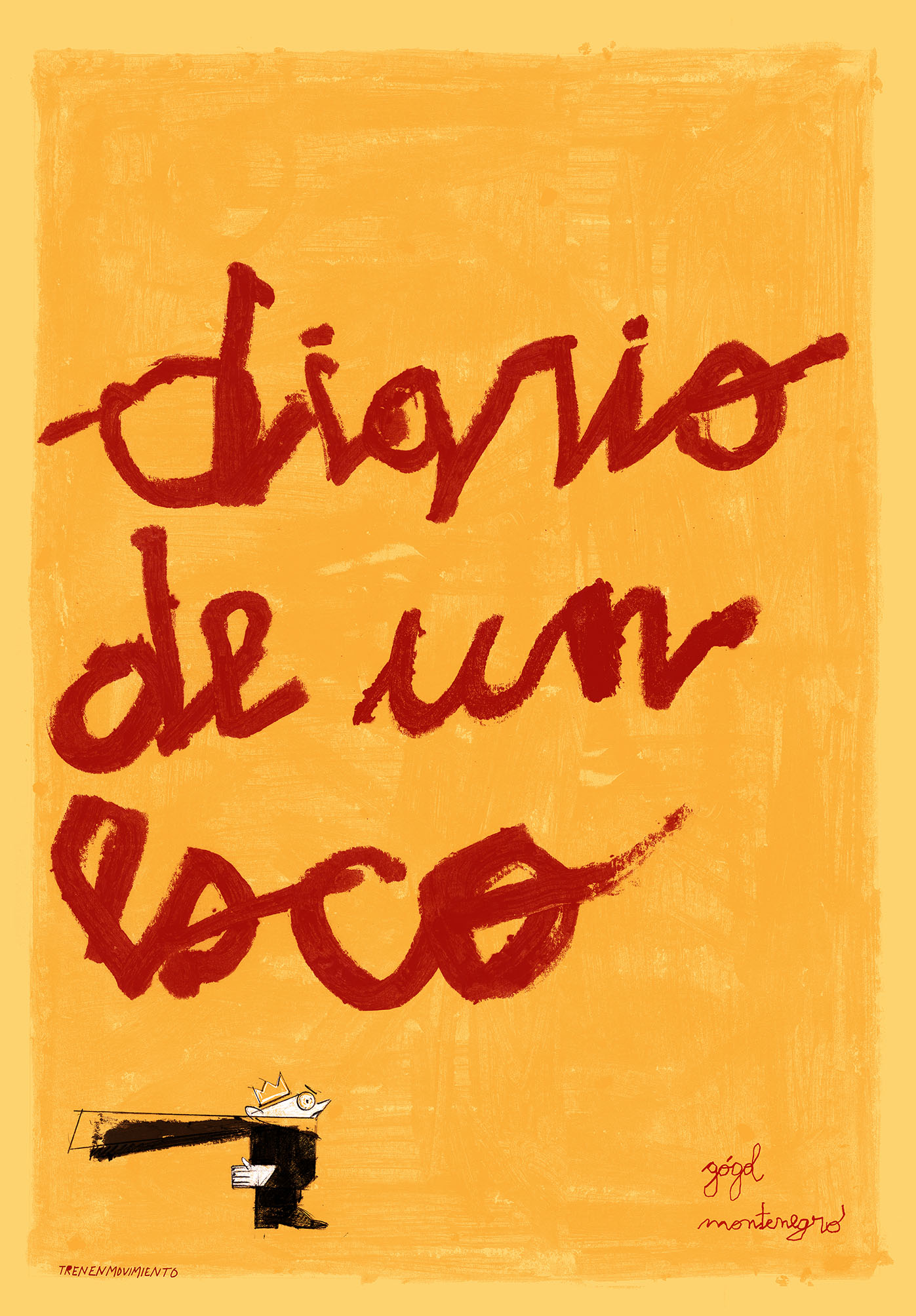

Diary of a madman

Argentina has an economic support program for translations for those publishers that purchase rights to books by Argentine authors. Click here for more information.

Original title: Diary of a madman

Writer: Nikolai Gogol

Illustrator: Christian Montenegro

Original Publication: Tren en Movimiento 2017

Format: 35 x 50 cm

About the book:

Diary of a Madman can be read on many levels, and I think that's where its power lies: literature's

transposition to comics -relationship on which Alberto Breccia, Christian's teacher, was indeed a

master-; time superposition between the story's real context -Nicholas I's Czarist Russia- and the

Soviet design -as well as, why not, 1917's revolutionary yearnings, those which proposed the thinking

early 20th century

American comics -another form of revolution, if you will.

It is clear that Montenegro chose a narration based on a predetermined grid (or page layout), a kind

of formal principle that organizes the story. However, none of the pages looks like the other. It's

understandable: to tell madness' tale, it's necessary to contain it -otherwise, the story would be

reduced to unintelligible glyphs. In which other way could this Diary's voice have been reproduced?

That voice which deteriorates progressively and rapidly until falling into total insanity...?

The main character, small Poprischin -a low-ranking civil servant- appears as the 20th century's

dreadful metaphor: this world is full of mediocre men, and they are essential mechanisms of every

machinery of control, repression and extermination. Somehow, Gogol anticipated acidly and accurately

what Kafka led to a point of no return.

In this way, there seems to be no possible escape, no cracks in the pavement. However, graphic

achievement here: resembling the gigantic format of the early 20th century newspapers -true control

devices of instructive capitalism-, we are given back some of that feeling readers might have enjoyed

while reading Herriman's Krazy Kat, Mc Cay's Little Nemo in Slumberland or Feininger's Kin-der-Kids,

among many others.

Laughter is subversive, like colors against concrete. How to encourage nowadays and attempt an

edition in such a format, with a story that entertains and desperate us? A gesture of creative exasperation,

which seems to have no place in this asphyxiating reality but, nevertheless, gains its place in

this world by force, leaving us the dilemma of knowing what to do with it.

Pablo Turnes